As cyber warfare has escalated in recent years, states increasingly seek and acquire a range of advanced cyber capabilities, from spyware to destructive malware. Demand for these capabilities has led to an explosion in the market for cyber mercenaries: private-sector actors who develop, provide, or support offensive or intrusive cyber capabilities for a fee. Already valued at $12 billion as of 2019, the cyber mercenary market is growing rapidly, resulting in a dramatic increase in exploitation of previously unknown security vulnerabilities, known as “zero-day” exploits. Absent meaningful international guardrails, this shadowy but robust industry has enabled human rights abuses, lowered the barrier to entry for advanced cyber weapons that can target critical infrastructure and institutions, and further complicated the already daunting challenge of cyber accountability.

Constituting Part 5 of FP Analytics’ Digital Front Lines special report, this issue brief assesses the scope and influence of the global cyber mercenary market, identifies the challenges of regulating it, and explores opportunities to mitigate its destructive impacts and strengthen international preparedness and response.

The Cyber Mercenary Market—A Broad and Evolving Array of Products and Participants

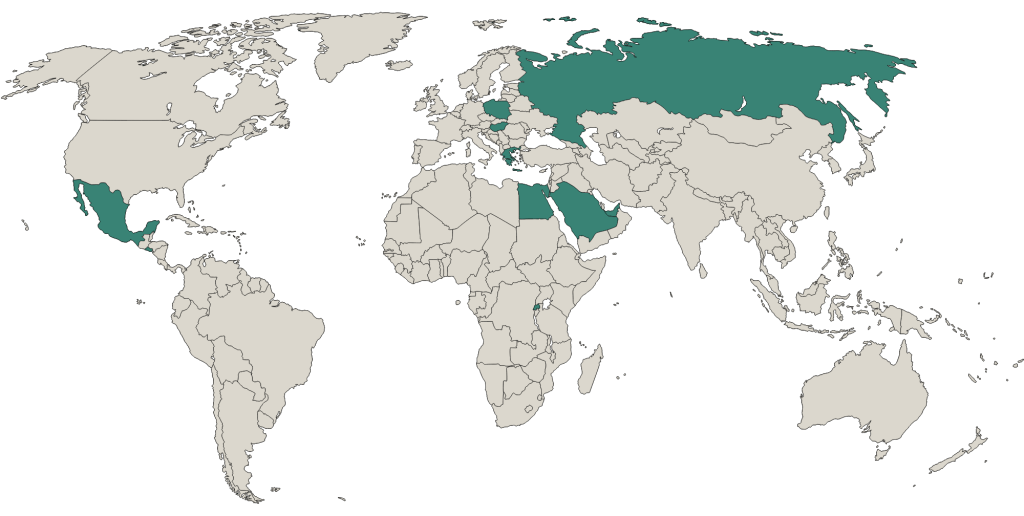

The market for cyber mercenaries includes a wide range of services, buyers, sellers, and motives, each of which may overlap with legitimate uses of cyber technologies. Buyers in the cyber mercenary market are often governments seeking to advance their security interests. Since 2011, at least 74 national governments have leveraged cyber mercenaries for the use of spyware alone. Cyber mercenaries may help states disrupt or destroy their adversaries’ infrastructure; censor, harass, or spy on political dissidents; profit from ransomware; or steal classified or proprietary information. Cyber mercenary services may appeal to governments because involving a third party can help conceal responsibility and avoid consequences for illegal and/or destructive behaviors.

Buyers can also be cyber criminals, or private actors hoping to spy on other nonstate actors, such as business rivals or romantic partners. While these buyers may not participate in hostilities, similar products, services, and vendors can be used for both purposes, muddying the boundaries of the cyber mercenary market. Cyber mercenaries employed by nonstate actors can be similarly disruptive to victims’ lives or destructive of civilian infrastructure as those engaged in hostilities between states.

Sellers in the cyber mercenary market—the mercenaries—are often small private firms that develop and sell sophisticated cyber capabilities, such as those featured in Graphic 1. One prominent example is the NSO Group: an Israeli firm that sells spyware technology to governments and has been accused of facilitating numerous human rights abuses, such as the targeting of Jamal Khashoggi and those close to him. Other firms, such as Zerodium, act as middlemen in the cyber mercenary market by buying technology from one firm, or from independent researchers, and reselling it to a separate customer.

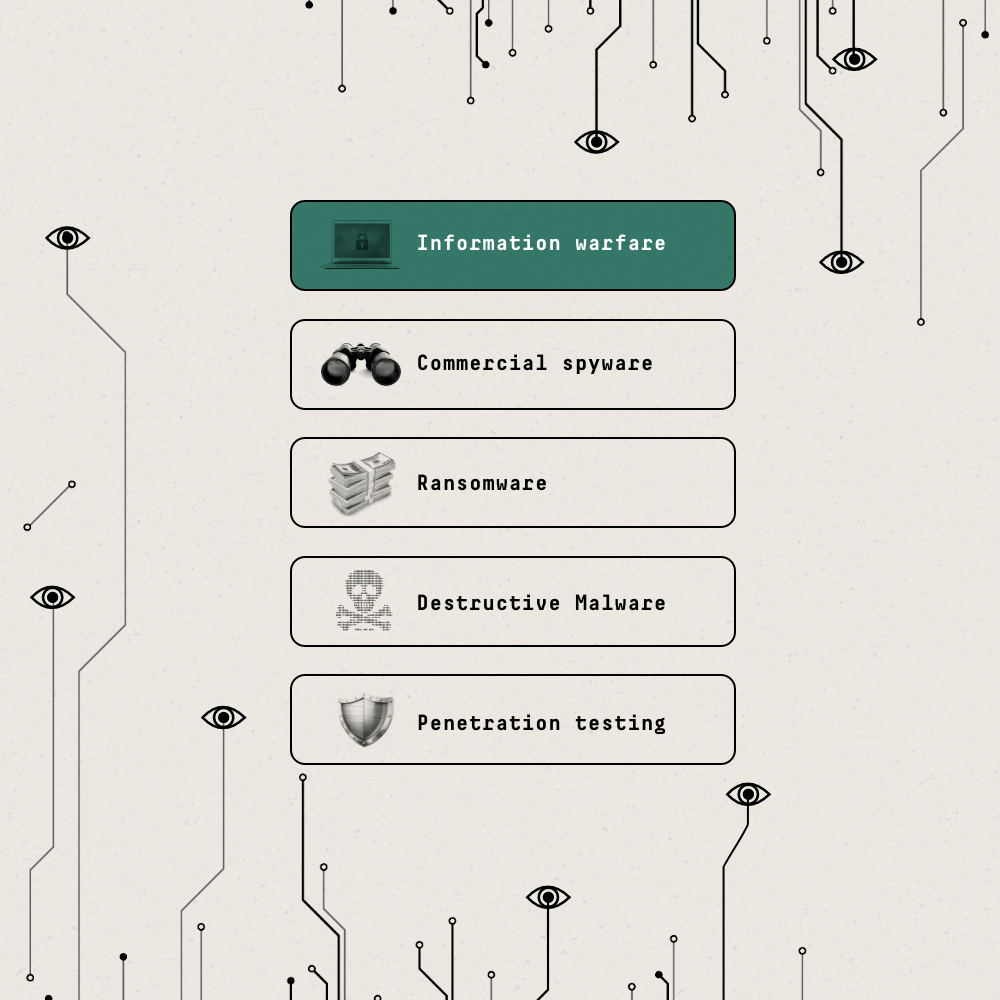

Products and Capabilities in the Cyber Mercenary Marketplace

The market for cyber mercenaries includes a broad and evolving range of products, services, capabilities, and operations. The below typology categorizes mercenary activity into five thematic bins, but specific techniques, companies, vulnerability exploits or software may span multiple categories.

Information warfare

Operations intended to gain an advantage over an opponent by controlling and manipulating information. Cyber mercenary firms may assist with influence operations—online efforts to influence the attitudes, behaviors, or decisions of a target audience—as well as censorship software to restrict what people can view or publish online.

Example: In 2024, the U.S. sanctioned a Canadian company called Sandvine for supplying deep packet inspection technology to Egypt, which helped block 600 websites.

Commercial spyware

Spyware monitors and extracts sensitive data from devices without the knowledge or consent of users.

Example: The NSO Group developed spyware called Pegasus that can be covertly and remotely installed on mobile phones, without requiring the user to click on a malicious link or message. Governments around the world have abused Pegasus to spy on journalists, activists, and political opponents.

Ransomware

Ransomware blocks access to a computer system until a sum of money is paid.

Example: Example: In 2023, total ransomware payments reached $1.1 billion.

Destructive Malware

Mercenaries may leverage cyberattacks to degrade an enemy state’s domestic infrastructure or military capabilities.

Example: In 2012, malware called Shamoon wiped the data of 35,000 computers at Saudi Aramco, the world’s largest oil company. A group of hackers called Cutting Sword of Justice claimed responsibility, but U.S. intelligence accused Iran of supporting the attack.

Penetration testing

The same tools used to exploit vulnerabilities in an adversary’s systems can also be used to identify and patch vulnerabilities in friendly networks, adding to the challenge of distinguishing legal and legitimate from illegal and irresponsible cyber capability vendors.

Example: Firms like CrowdStrike and Mandiant offer penetration testing and red teaming services, wherein ethical hackers conduct a simulated and nondestructive cyberattack, to government clients.

Prominent Commercial Spyware Incidents

One of the most pervasive products found on the cyber mercenary market is spyware, which is often used to gain access to sensitive data from a target’s phone or digital device. Spyware can obtain a user’s emails, text messages, calendar, contacts, photos, and anything else appearing on screen, as well as activate a device’s camera or microphone to record a user without their knowledge. Spyware is deeply invasive and can be used to obtain endangering or damaging information about the target, which may produce a chilling effect on those targeted, including on political dissidents’ willingness or ability to speak out. However, spyware is only one of the products and capabilities sold on the cyber mercenary market, and by no means the only threat that cyber mercenaries pose.

Mercenaries have varying degrees of involvement in the cyber operations they enable. They may be paid to carry out the operation directly, to provide a tool or exploit kit for the buyer to use to conduct the operation, or to reveal knowledge of a vulnerability that the buyer may exploit with their own tools. With so many different types of buyers, sellers, products, services, and degrees of private-sector involvement in state operations, the cyber mercenary market is continually evolving and defies neat categorization. However, underpinning the entire market is the discovery and exploitation of software vulnerabilities as a business model.

Regulating Cyber Mercenaries is a Challenge Requiring International, Cross-Sectoral Cooperation

Cyber mercenaries present unique and complex challenges for regulators, beyond those presented by traditional mercenaries. First, hackers are highly mobile and can work from anywhere, creating jurisdictional obstacles to bringing them to justice. If a mercenary outfit is shut down in one place, its members can reconstitute where legal restrictions are few, weak, or poorly enforced. For example, when Israel tried to crack down on some cyber mercenaries operating within its territory, the individuals driving those operations simply moved to states like Spain, Cyprus, North Macedonia, and Turkey to circumvent regulation. Thus, lasting solutions require interstate cooperation and standardization of relevant regulations across borders.

Second, there is a significant overlap between what may be legitimate uses of the relevant hacking techniques and clear abuses. So-called “white-hat” hackers in the private sector may use commercial tools to detect vulnerabilities in a client’s systems so that they can be patched. Even some offensive cyber operations supported by mercenaries may be seen as a legitimate form of statecraft, such as wartime cyberattacks destroying military infrastructure, which would otherwise be legal to destroy using conventional munitions. Smaller states, especially, may struggle to develop cyber capabilities in-house and see mercenary firms as a way to match the capabilities of more powerful states. Because many governments want to use these tools to advance their security interests, efforts to establish guardrails on the use of cyber mercenaries and achieve international consensus on the appropriate scope of private cyber operations need to be realistic about which cyber capabilities states will be willing to forfeit.

Third, while conventional military capabilities require trackable equipment like tanks, missiles, or aircraft, hacking capabilities are largely knowledge-based and highly transferrable from governments to firms. This makes it harder to monitor the proliferation of cyber capabilities that states develop internally, and in turn, harder to hold states accountable for disruptive and destructive capabilities they unleash through the private sector. Individuals trained for legitimate purposes may, upon leaving government, sell their skills to the highest bidder in defiance of the law or of ethical standards. To address this problem, tightening regulations to prohibit the market and strengthening accountability measures may be necessary to prevent former employees who have been trained on dangerous cyber techniques from selling their skills and expertise on the cyber mercenary market.

There are also legal and practical challenges to confronting cyber mercenaries. Some mercenary groups have argued that the legal principle of sovereign immunity, which protects governments from being sued, should extend to private actors selling to government clients. Depending on the national or international laws applied, this long-running legal debate may hinge on contextual factors such as the firms’ degree of involvement in cyber operations; the firm’s willingness to name the state serviced, and that state’s willingness to confirm the nature of the relationship; or the involvement of a state’s sovereign property or protected activities. Because the sale of cyber mercenary services is typically not disclosed to the public, expansive interpretations of derivative sovereign immunity present challenges for accountability and oversight.

Technological change in the digital realm is accelerating, including through the integration of artificial intelligence in the cyber mercenary market. Such rapid change often outpaces the grinding process of passing legislation or international agreements. Finally, because software is merely the text of computer code, it can often be broken down into harmless components that escape regulation, only to be reassembled elsewhere to execute a harmful function. In combination, these factors complicate any efforts to regulate the cyber mercenary market or mitigate its destructive impacts.

Emerging Global Efforts to Reign-In Cyber Mercenaries are Promising but Need to Be Bolstered

Despite a range of complex challenges, several international efforts to address the harms of the cyber mercenary market spanning the public, private, and multilateral sectors are underway. In 2022, the Paris Call for Trust and Security in Cyberspace convened a working group on cyber mercenaries, which released a Multistakeholder Blueprint Towards Increased Transparency and Cyber Stability last year. The Blueprint includes 12 priority recommendations aimed at governments, companies, and industry partners to address the greatest risks presented by cyber mercenaries. The recommendations build on industry principles developed by the Cybersecurity Tech Accord (CTA), a coalition of tech companies. The CTA now tracks which governments adopt policies consistent with the Blueprint’s recommendations, boosting accountability.

Also in 2022, the European Union (EU) launched the PEGA Committee to investigate member state and third-party abuses of intrusive surveillance software. The committee’s final report recommended safeguards, conditions, and export controls on commercial spyware. Although the recommendations from the PEGA Committee and the Paris Call are a promising first step toward accountability, both sets of recommendations are ultimately nonbinding and have yet to be fully implemented. Firmer commitments from all stakeholders are needed to build on the momentum of the Paris Call and PEGA Committee in order to convert that momentum into action.

In a more assertive and unilateral approach, the United States has taken a series of punitive and preventative measures combatting commercial spyware. In November 2021, the U.S. Department of Commerce imposed trade restrictions on four cyber mercenary companies, including the NSO Group. These sanctions were followed by visa restrictions on individuals affiliated with these companies in February 2024. In March 2023, President Biden issued an executive order barring U.S. government entities from purchasing commercial spyware that endangers security or human rights. The same week, the U.S. led a joint statement, now supported by 21 nations, committing to export controls on abusive spyware, among other steps.

Direct action to deter and limit the use and sale of commercial spyware is a welcome complement to ongoing international dialogue, and some U.S. allies have begun to emulate this tougher approach. For example, in 2023, Germany filed charges against four individuals involved with the FinFisher Group, which had illegally sold intrusive surveillance software to Turkey. The German investigation resulted in the FinFisher Group ceasing operations, demonstrating that direct action from governments can be effective. However, due to the ability of hackers to reconstitute where regulations are lax, long-term solutions will also require international coordination.

To advance such coordination, in February 2024 the United Kingdom and France began the Pall Mall Process (PMP) for tackling the proliferation and irresponsible use of commercial cyber intrusion capabilities. Bringing together representatives of 25 states, two international organizations, 14 private industry stakeholders, and a range of academic and civil society organizations, the PMP aims to establish shared guidelines and policy options through an inclusive global process rooted in existing UN principles and multistakeholder participation. The first step in the Process was the Pall Mall Declaration, which defined key terms and proposed an initial list of four principles that could serve as a normative framework guiding international action: accountability for violating the law, precision in the use of cyber capabilities, oversight of users and vendors, and transparency in business interactions. While U.S. action has largely been unilateral and focused on commercial spyware, the PMP aims to address the full suite of commercial hacking tools by forging a global consensus.

Filling Gaps in the Global Response: Recommendations for the Public, Private, and Multilateral Sectors

The Pall Mall Process is the most comprehensive international effort to address the cyber mercenary problem to date. Its organizers have initiated the painstaking, but necessary, work of building international consensus behind cyber mercenary norms. However, to succeed in reducing the threats that cyber mercenaries pose to human rights and global security, current efforts will need to be broadened, harmonized, and followed by concrete action.

At present, the PMP is limited by its focus on “commercially available” capabilities, an undefined term that may exclude capabilities sold solely to government clients. Specifically, the Declaration refers to “off-the-shelf” products that are accessible to “the general public,” which may not affect companies like the NSO Group, which work exclusively with governments. Likewise, it excludes government-to-government capability transfers like Project Raven—a group of former U.S. intelligence operatives found to be helping the United Arab Emirates to spy on citizens of both countries—as well as free or noncommercial intrusion capabilities and dual-intent tools used for password cracking, network scanning, or remote access. Efforts to combat cyber mercenaries will be of limited impact if they fail to address the leading role governments play in fueling the market, both by hiring cyber mercenaries directly and by developing offensive cyber capabilities in-house that eventually trickle into the commercial market.

There are also tradeoffs to broad participation in the PMP, since some actors may have a vested interest in thwarting, thinning, or slowing progress on norms prohibiting their behavior. For example, Greece is a signatory to the PMP, even though the PEGA Committee Inquiry called out the country for purchasing spyware for purposes of political suppression. The government of Singapore is also a signatory, but the city-state is emerging as a cyber mercenary hotspot. To strengthen accountability, it may be necessary to apply more pressure on governments that are hosting or funding unethical vendors or supplying a pipeline of hacking talent to vendors in other countries.

Finally, PMP leaders and signatory nations do not need to wait until the Process has completed to act against cyber mercenary firms. Imposing sanctions against commercial spyware vendors, comparable to those levied by the United States, could help France and the United Kingdom lead by example and build momentum toward norms proscribing abuses of software like Pegasus. Apart from reactive sanctions against bad actors, PMP nations could also fuse their emphasis on multistakeholder engagement with concrete and proactive regulation. As a step in this direction, the PMP could specify a list of actions necessary for state and nonstate participants to comply with their consensual guidelines; create a shared timeline for their execution; and require participants to commit to certain standards of enforcement.

EU nations can enact legislation following the recommendations of the PEGA Committee, such as tightening controls on dual-use cyber tools, which the PEGA report called “weak and patchy.” The recently begun Polish Presidency of the EU is well placed to lead on spyware regulation by building on Poland’s ongoing internal investigation of the prior Polish government’s abuse of the technology. The United States could strengthen its own sanctions regime by designating spyware vendors as human rights abusers under the Magnitsky Program.

States could also pass legislation narrowing or clarifying doctrines of sovereign immunity, ensuring that vendors of cyber tools may be held legally responsible for confirmed misuses of their products. To avoid fueling the supply or demand for cyber mercenaries, governments can develop their own cyber tools when possible, share them only with responsible partners, and prosecute individuals who share them elsewhere upon leaving government. They also need to thoroughly vet any companies that they purchase cyber tools from, to avoid contracting with enablers of human rights abuses. For their part, private companies can inform and comply with potential sanctions against cyber mercenaries while investing in secure-by-design products and cybersecurity awareness. Civil society organizations such as The Citizen Lab and Amnesty Tech can continue to shed light on abuses of commercial spyware, help victims recover their data or privacy, and advise policymakers on evolving risks and trends in the cyber mercenary market.

Looking Ahead

As nations gather in Munich for the 61st Munich Security Conference, security leaders and strategists grapple with a rapidly changing global order—an order already strained by armed conflicts in several regions. In order to contain these conflicts and produce an enduring peace, however, leaders will also need to manage the risks of irregular conflict axes such as cyber warfare. Central to this task will be mitigating the harms of cyber mercenaries, which frustrate accountability for state conduct, enable persecution of political dissidents, and increase the volume of destabilizing cyberattacks. The borderless and amorphous nature of the cyber mercenary market will require coordination among sectors, nations, and multilateral negotiating bodies for mitigation to succeed. By confronting the role of governments in fueling the market, building on existing diplomatic initiatives, sharing threat information across sectors, enacting and complying with needed regulations, and pursuing consensus and action in tandem, the global community can better contain the threat of hired hackers while establishing norms to secure and stabilize cyberspace.

By Andrew Doris (Senior Policy and Research Analyst) and Dr. Mayesha Alam (Senior Vice President of Research).

This issue brief was produced by FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, with support from Microsoft. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of this issue brief. Foreign Policy’s editorial team was not involved in the creation of this content.