Despite an established pattern of cyber operations against Ukraine dating to at least 2013 and warnings of an impending “cyber-Armageddon,” Russia’s cyber offensive since the full-scale invasion in February 2022 has found limited success. While it is likely that some operations—for example, those in the priming stages, including surveillance—have gone undetected or unreported, Ukraine’s cyber resilience has, with international support, largely prevailed in the face of sustained Russian cyberattacks against the government and population. This issue brief, produced by FP Analytics with support from Microsoft and launched alongside the 2023 NATO summit, analyzes the international community’s multisector collaboration to respond to Russian cyber operations and strengthen cyber capacity. Beyond insights on Ukraine, the successes and challenges examined here can inform preparation for future cyber–kinetic conflicts.

As Russian Cyberattacks Ramped Up, Ukrainian Actors Accelerated Response Times

The Ukrainian responses to three similar attacks on the electrical grid since 2015 show significant improvements in cybersecurity protocols by critical infrastructure operators.

Data sources: E-ISAC, International Security, Reuters, New York Times

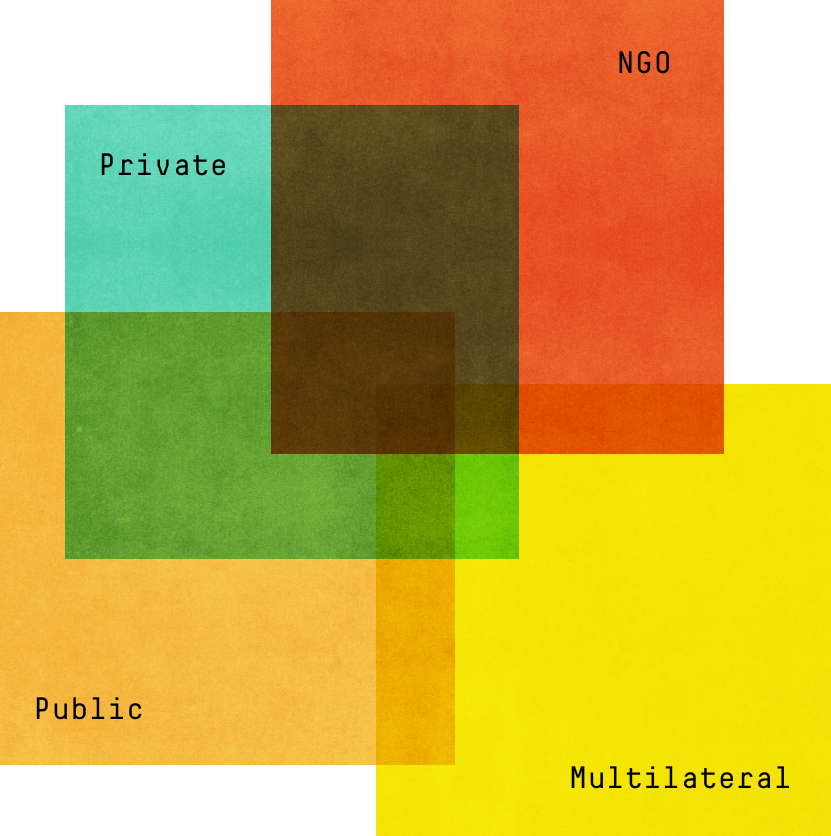

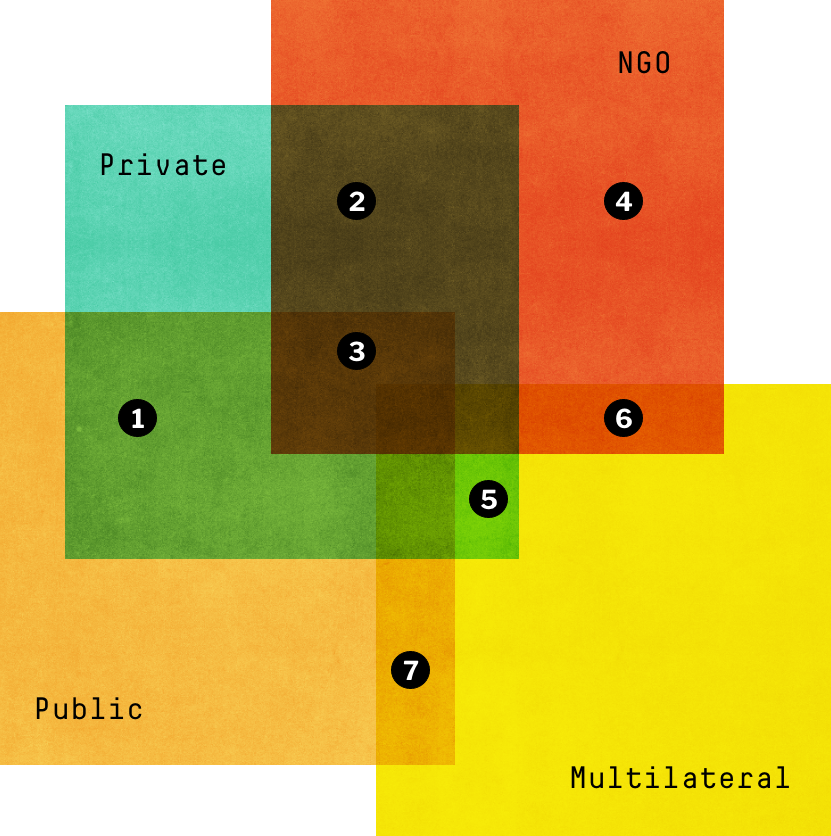

Ukraine has continually built up and adapted its cyber defense capacity since Russia annexed Crimea in 2014. As a result, the country has significantly deterred, defended against, and mitigated the cyber destruction that Russia and its proxies have unleashed in the past year and a half. Notably, a range of international actors have helped to cultivate and bolster Ukraine’s existing cyber resilience through technical, financial, diplomatic, and legal avenues. International governments, along with private-sector companies, multilateral institutions, media outlets, and civil society stakeholders, have partnered with one another and Ukrainian actors to prevent and blunt the effects of cyberattacks. In particular, the private sector’s level of involvement has been unprecedented; multinational companies have directed their technology and expertise to aid Ukraine, responding to Russian cyber operations by countering mis- and disinformation, including through public reporting on malicious activity, providing access to proprietary technology, building digital capacity, and assisting in the design of cybersecurity strategies.

Multiple Sectors Coordinated Responses to Cyberattacks Targeting Ukraine

As these examples illustrate, the international response to cyber operations in Ukraine has brought together actors from across sectors to respond creatively to cyber threats.

Data sources: Bloomberg, The Guardian, Microsoft, Spravdi Ukraine, Conflict Observatory, CyberPeace Institute, Government of Canada, Bellingcat, UC Berkley Human Rights Center, OpinioJuris, UNDP

In-Kind Contributions Have Strengthened Ukraine’s Cyber Resiliency

The international community has mobilized to protect Ukraine’s ground and digital defenses in numerous ways, including offering subject-matter expertise and intelligence to protect critical infrastructure and government data. These efforts demonstrate models for cyber cooperation on a cross-sectoral and sub-government level. In the months before Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine, an EU-U.S. cyber response team was dispatched to Ukraine to detect active cyber threats and build defensive capacity. Individual U.S. government agencies have also leveraged existing relationships and established partnerships to develop cybersecurity and connectivity in the Ukrainian private sector. The U.S. Department of Energy, for example, has worked closely with the energy sector in Ukraine to increase cyber defenses and alleviate damage; the U.S. Treasury has likewise supported the National Bank of Ukraine for the past several years to improve cybersecurity and information-sharing across the financial services sector, guarding against such attacks as 2017’s NotPetya. Additionally, the U.S. Agency for International Development (USAID) has provided emergency technological support—including more than 6,750 communications devices, such as satellite phones and data terminals—to government agencies, critical infrastructure operators, and emergency services to stanch the crippling effects of repeated cyberattacks on telecoms infrastructure.

Alongside digital capacity-building and in-kind contributions from allied governments, Ukraine’s cyber defense has also benefited significantly from far-reaching private-sector efforts to provide technical assistance and proprietary services. The Ukrainian Ministry of Digital Transformation has maintained a close partnership with companies including Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, Google, Oracle, and Starlink. In particular, the rapid action taken to evacuate Ukrainian government data to remote servers and the cloud demonstrates the impact of public–private collaboration to safeguard data digitally and physically. Some tech companies have likewise supported the Ukrainian private sector at reduced or no cost. Microsoft has provided cloud-computing platforms to companies including Kernel, Ukraine’s largest producer of sunflower oil, and KredoBank in order to bolster critical infrastructure resilience. In July 2022, Cloudflare offered free rapid cyber defense services to more than 60 Ukrainian businesses that were concerned they had been breached by Russian hackers. The expertise, capacity, and agility of the private sector have been critical to safeguarding Ukrainian cyberspace and public and private data.

Rapid, Collaborative Efforts Supported the Safe Evacuation of Ukrainian Government Data to the Cloud

A timely private–public partnership moved critical government information and operations to the cloud just before the Russian invasion.

Data sources: Microsoft, The Stack, Foreign Policy, Insider, TechRadar

Pre-February 17, 2022

Up until one week before Russia’s full-scale invasion, Ukrainian government operations were entirely located in on-premise servers. Ukraine’s data protection laws—like those of many other countries—prohibited processing and storing government data in the public cloud.

February 17, 2022

Following Vice Prime Minister and Minister of Digital Transformation of Ukraine Mykhailo Fedorov’s advocacy, Ukrainian parliament amended data protection laws to allow evacuation of critical government data.

February 17, 2022–December 2022

A coalition of tech companies partnered with the Ukrainian government to move information and operations to the cloud. Microsoft committed $107 million in technology support, including cloud data storage solutions. Amazon Web Services was also pivotal to these efforts, physically transporting data servers into Ukraine and then back over the border once information had been transferred, before uploading data onto the AWS cloud.

February 24, 2022

These efforts were timely and impactful. On the first day of the invasion, Russian missiles targeted a Ukrainian government data center while Russian wiper cyberattacks also targeted government on-premises networks.

Early May 2022

Much of the Ukrainian government’s essential digital operations and data were transferred to the cloud, including the work of 20 ministries and more than 100 state agencies and state-owned enterprises.

By the end of 2022

An estimated 10 million gigabytes of Ukrainian government data were being stored on cloud-based platforms. According to Minister Fedorov, more than 100 state databases have been transferred to servers across Europe, and onto cloud platforms, although Ukraine has been careful not to disclose where servers are located.

International Financial Support Has Buttressed Ukraine’s Cyber Defense

The direct funding that Ukraine has received, particularly from governments, has been invaluable in supporting Ukraine in custom-building its cybersecurity infrastructure to better defend against Russian operations. Public-sector and multilateral donations and financial support have included a focus on such critical infrastructure as telecoms, internet, and health services. These donations also included funding to connect Ukrainian government agencies to commercial cybersecurity companies and foster partnerships with tech companies to deliver the necessary resources and support.

Nongovernmental organizations have also taken steps to directly fund Ukraine’s cyber response. For example, U.S.-based nonprofit UkraineNow.org originally focused on directing public donations to refugees but expanded its remit in August 2022 to include fortifying cybersecurity infrastructure. The global public can now donate directly to support the purchase of stronger login credentials for Ukrainian government agencies including the National Police, the Ministry of Digital Transformation, and government-owned energy and power plants. By contrast, while private-sector companies have donated significant sums to humanitarian and civil society organizations active in Ukraine, few, if any, have specifically directed funds toward cyber defense. Instead, with a few exceptions, contributions to Ukrainian cyber resilience have largely taken the form of in-kind donations of services and technologies.

Diplomatic Actions Have Targeted Russia’s Cyber Capacity, While Bolstering Ukraine’s

International support for Ukraine has taken various forms beyond financial and technical assistance. Many international actors have responded to Russian aggression in Ukraine by using their diplomatic clout to condemn Moscow and impose punitive measures, including for acts of cyber aggression. Furthermore, states including Australia, Japan, Norway, South Korea, the United States, and the United Kingdom have imposed restrictions to weaken Russia’s technical capacity to launch cyber operations, limiting exports to Russia of dual-use tech products such as semiconductors, information security equipment, lasers, and sensors. Of note, some sanctions have targeted Russian organizations and individuals, including those to which cyberattacks were attributed prior to the war. The EU has regulated cyber activity, sanctioning Russia’s tech sector, prohibiting IT consultancies from working in Russia, and prohibiting Russian nationals from holding executive positions in EU critical infrastructure. A range of multinational companies have likewise isolated Russia’s cyber infrastructure in line with sanctions. Tech companies including Apple, ESET, and Microsoft significantly scaled down services from the Russian and Belarusian markets following the full-scale invasion. Engineering software companies including Autodesk, Dassault Systèmes, and PTC have done the same.

Diplomatic responses have not only isolated Russia but also have rallied around Ukraine. The North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) responded to cyberattacks in Ukraine by strengthening diplomatic ties with Kyiv and committing to increased investment in regional cybersecurity. Days after Russia’s invasion, NATO upped its diplomatic deterrence by reiterating that a cyberattack could trigger collective defense through Article 5. Furthermore, NATO admitted Ukraine to its Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence—which conducts training and research and hosts the world’s largest international cyber defense exercises—in January 2023 as a “Contributing Participant.” This invitation demonstrated a creative solution for supporting Ukraine while avoiding the governance challenges associated with adding new members to the alliance. Still, many multilateral institutions have been constrained by institutional challenges, such as the inability to use existing conventions in situations below the threshold of war, and Russia’s veto power in the U.N. Security Council.

Prosecution of ‘Cyber War Crimes’ Could Set Precedent for Future Conflicts

International actors have also been engaged in a dynamic legal effort to hold Russia accountable for its cyber actions and establish norms for future cyberattacks. In 2021, NATO’s Cooperative Cyber Defence Centre of Excellence launched the Tallinn Manual project, the world’s most comprehensive effort to codify international norms regulating cyber behavior and identify important areas of nonconsensus for further investigation. The UC Berkeley Human Rights Center partnered with the UN Human Rights Office to launch the Berkeley Protocol in January 2022 to guide the verification, collection, and analysis of open-source intelligence for use in international investigations, including distributed-denial-of-service attacks, phishing attacks, malware, and other cyberattacks.

Further leveraging international law, the Human Rights Center formally requested in May 2022 that the International Criminal Court (ICC) indict a Russian-backed group for the targeting of civilian utilities in Ukraine, urging the prosecutor to include cyberattacks in his investigations. In March 2023, the center submitted its second request to the ICC, arguing that the ICC should investigate five Russian cyberattacks due to their indiscriminate nature and targeting of civilian objects. While there is currently no consensus on whether cyberattacks qualify as war crimes under existing statutes, if taken forward, these complaints would be the first instances of the ICC investigating cybercrimes and could lead to new efforts to adapt international humanitarian law to hybrid warfare in the digital age.

Preparing for the Next Hybrid War

Aided by a rare Western consensus on Russian aggression, the ongoing war in Ukraine has led to novel multisector collaboration to deter and respond to cyber operations and build long-term defenses. Exceptional levels of private-sector involvement have significantly enhanced cybersecurity but have also elevated new challenges. Norms around responses to cyber operations are in the process of being established, but the lack of clear guidelines creates difficulties for all actors, including how to work collaboratively across sectors. For instance, mutually agreed expectations have not yet been established for public-private partnership in cyber warfare, and potentially divergent aims and motivations could create a disconnect between public and private interests.

The private sector’s close involvement in the formulation and implementation of cyber defense policy can simultaneously create opportunities and raise ethical challenges. While there are normative reasons for companies to act against Russian cyberattacks, private entities can also benefit from high-profile international responses through reputational boosts and product exposure. Furthermore, operational difficulties may arise if companies’ profit motives or shareholder responsibilities prevent them from offering technology and expertise indefinitely. If the beneficiaries of in-kind aid do not adapt rapidly, or if other partners do not step in to assist, an unplanned or rapid withdrawal has the potential to leave cyber defenses exposed. Governments stand to benefit from strategic planning to sustainably maintain long-term cyber capacity and support, including creating mutually agreed expectations for private-sector involvement without over-relying on companies for services and technology.

The collective response to the Russian invasion has showcased new strategies to prepare for, and respond to, future wars in which cyber operations could play an even greater role; as such, there is much to learn from the ongoing innovation and collaboration taking place in Ukraine. The input and support of international partners—from multilateral institutions and foreign governments to the private sector and civil society—demonstrate the potential impact of a whole-of-society, consensus-driven approach to defense against information warfare and cyberattacks. Cross-agency intelligence-sharing and technical assistance can effectively build upon existing intergovernmental relationships and create new alliances. Critically, the private sector can provide vital expertise, creativity, and manpower in providing cyber defense services and capabilities. Furthermore, the Russia–Ukraine war—and the preceding decade of cyber operations—underscore the need for long-term cyber strategies to manage the emergence and escalation of potential future instances of cyber–kinetic conflict in geopolitical hotspots such as China, Iran, or North Korea.

The lessons learned from Ukraine’s cyber resilience and the cooperative multisectoral support of the international community can be drawn upon to prepare for future cyber threats around the world:

- In December 2022, the EBRD partnered with a Ukrainian global cybersecurity service provider (ISSP) to share best practices and lessons learned to enhance the cybersecurity of businesses in Moldova—a country that has experienced a dramatic rise in cyberattacks since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine.

- Estonia is working with Ukrainian partners to adapt and implement Ukraine’s resilient online platform for public services and data storage.

- In the Dominican Republic, the Latin America and Caribbean Cyber Competence Centre is elevating lessons learned from Europe, including Ukraine, to assist regional governments in developing cyber strategy and capacity.

- NATO’s 2022 Strategic Concept, which defines the security challenges facing the alliance and outlines the efforts needed to address them, includes such tasks as enhancing cyber defenses, networks, and infrastructure; increasing investment in emerging technology and cooperation with the private sector; and developing standards to protect democratic values and human rights in cyberspace.

While these initiatives are promising, there is much to be done, not only to further support and strengthen cyber defenses but also to improve communication, coordination, and collaboration globally in the age of hybrid warfare.

By Isabel Schmidt (Senior Research and Policy Analyst), Avery Parsons Grayson (Senior Risk and Policy Analyst), and Dr. Mayesha Alam (Vice President of Research).

This issue brief was produced by FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, with financial support from Microsoft. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of this issue brief. Foreign Policy’s editorial team was not involved in the creation of this content.