Hybrid warfare, the use of nonmilitary tactics alongside conventional kinetic warfare to achieve foreign policy goals, is hardly a new phenomenon. However, Russia’s use of hybrid warfare techniques in Ukraine—particularly cyber operations—is unprecedented in scale and scope. Cyber operations, the use of digital technology to surveil, disrupt, corrupt, or destroy government, civilian, and information infrastructure, are a rapidly evolving and increasingly common method of attack, constituting a key domain of hybrid warfare. The frequency and variety of cyber operations in the ongoing Ukraine war have underscored the urgency of not only better understanding their manifestations but also identifying strategies to mitigate their destructive impacts.

Produced by FP Analytics with support from Microsoft, this issue brief analyzes the evolution of cyber operations in contemporary armed conflicts. It underpins a broader three-part multicomponent research and data visualization project featuring analysis from FP Analytics alongside expert insights from luminaries across the public, private, and nonprofit sectors around the globe. Taken together, the Digital Front Lines project brings sharpened focus to the compounding risks, emerging implications, and key opportunities related to the challenge of hybrid warfare.

Unpacking Cyber Operations in Armed Conflict

States have been selectively deploying cyber operations for more than a decade as part of their geopolitical strategy and to advance foreign policy goals—for example, when the United States and Israel reportedly deployed Stuxnet malware in 2010 to destroy 20 percent of Iranian nuclear centrifuges. One key reason that governments deploy cyber tactics is their plausible deniability—compared to conventional military action—which enables them to compel adversaries without triggering all-out war. Increasingly, however, including in Ukraine, cyber operations are being used as a prelude to, or alongside, military operations.

In Ukraine and elsewhere, threat actors are unleashing cyber operations to immobilize government services, sabotage critical infrastructure, disrupt elections, and achieve other objectives. In armed conflicts, threat actors are leveraging cyber tactics to augment kinetic operations. Moreover, threat actors are wielding cyber operations—such as those that generate and amplify disinformation—to weaken and undermine social cohesion, exacerbating political fragmentation.

Different Types of Cyberthreat Actors

A threat actor is any organization, person, or group that directs or facilitates an attack in cyberspace to cause harm against a specific target, including state and nonstate entities. Within the targeted organization, agents may be recruited by threat actors to serve as “insider” operatives who are motivated by profit or personal grievance and/or sympathetic to a political cause.

- States: Operatives within a country’s government, including, for example, military and intelligence agencies that direct cyber operations as part of the broader conduct of foreign policy.

- Cybercriminals: Nonstate actors, both individuals and groups, who conduct cyber operations primarily motivated by profit.

- Hacktivists: Nonstate actors with a political motive, who limit their activism to the cyber domain. They may or may not be sympathetic to a particular state.

- Terrorist groups: Nonstate actors who are ideologically motivated and often seek to sow discord or spread influence campaigns alongside physical attacks.

- Cyber mercenaries: For-hire, private cyber operatives who are contracted by a state or nonstate actor for a specific operation or for the sale of specific technology.

In recent decades, cyber operations have played a central role in “gray zone” tactics, in which state parties to a dispute maintain high-level diplomatic relations while interacting antagonistically below the threshold of war. Nonstate threat actors may act independently or be affiliated with, and supported by, governments.

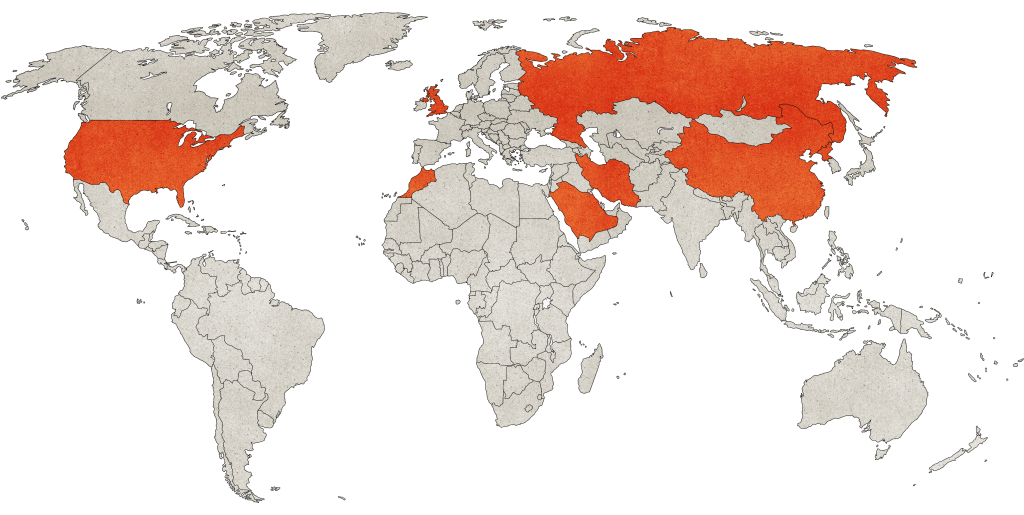

Cyber Operations Are Not Solely a Russian Domain

As these examples illustrate, various threat actors use cyber operations for information warfare, high-publicity diplomatic statements, surveillance, and other goals.

Data sources: Defense One, Middle East Eye, The White House, Acronis, BBC News, Canadian Medical Association Journal, BBC News, Sky News, U.S. GAO, TechTarget, Reuters, Politico, Amnesty International, Business & Human Rights Resource Centre, The Washington Post, Insider, Council on Foreign Relations, Microsoft

As cyber operations have become increasingly sophisticated and widespread, it is imperative for policymakers, business leaders, technical experts, civil society groups, and other stakeholders involved in addressing and mitigating cyberattacks to recognize and understand these tactics within the frame of hybrid warfare. Doing so is critical to avoid falling behind on the latest cyber developments and to foster collaboration to counter those threat actors who deliberately and indiscriminately harm civilians and civilian infrastructure for geopolitical advantage.

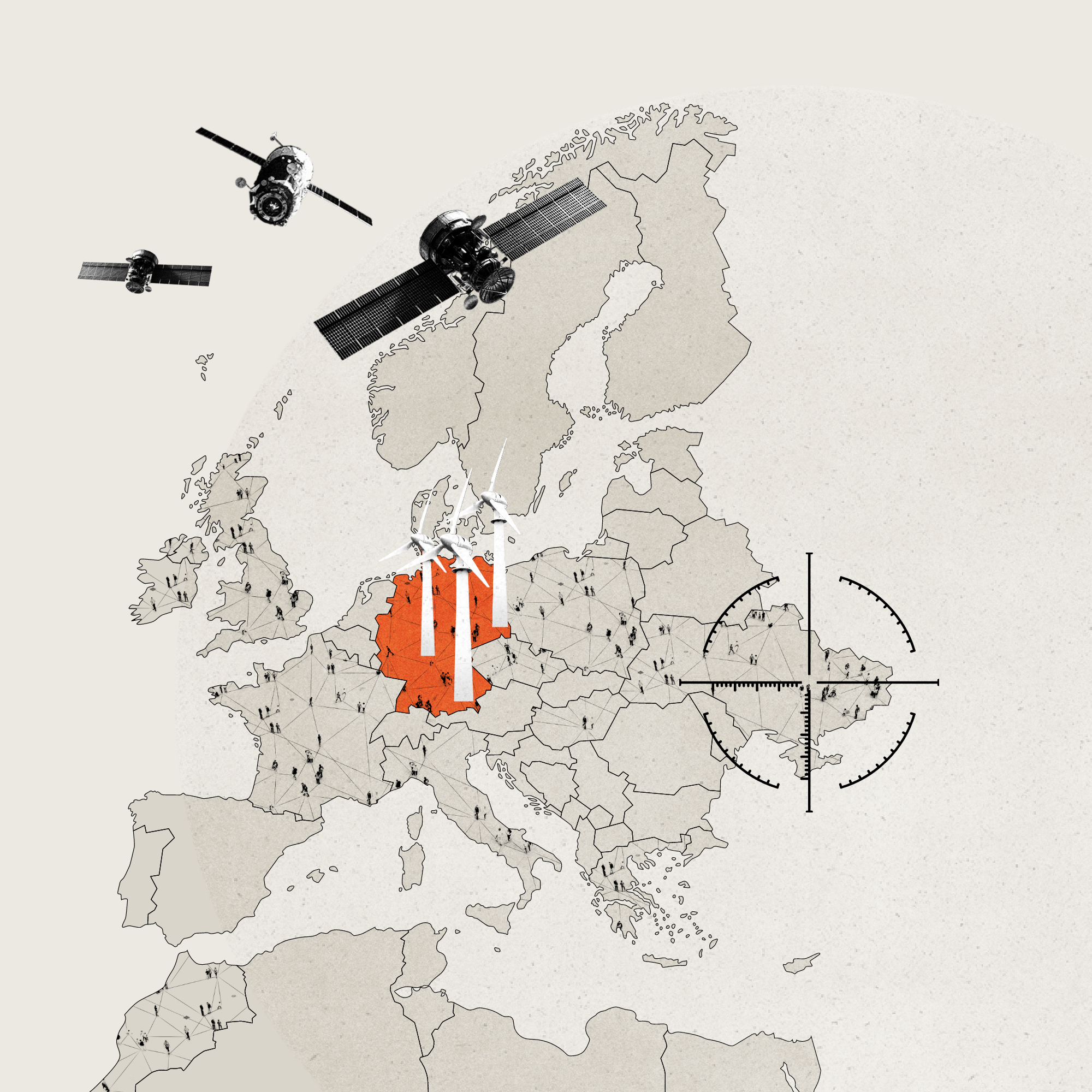

Disruptions Across Europe from Russian Satellite Hack

A cyberattack on the Viasat satellite network just hours before the Russian invasion of Ukraine had a cascading effect across the region.

Data sources: CSO, Council of the European Union, CyberPeace Institute, La Depeche, Wired, Reuters, Zero Day

Impact on military infrastructure

Satellite military communications in UKRAINE were disrupted.

Impact on energy sector

GERMAN energy company Enercon reported losing remote monitoring and control of 5,800 wind turbines across central Europe.

Impact on civilian internet access

Tens of thousands of civilians in UKRAINE lost internet signal for up to two weeks, impeding access to reliable information.

At least 27,000 users were impacted by the internet outages in the CZECH REPUBLIC, FRANCE, GERMANY, POLAND, THE UNITED KINGDOM, and OTHER EU COUNTRIES. In France alone, 9,000 subscribers lost internet.

Customers reported internet outages as far away as MOROCCO.

How Russia’s Sustained Cyber Campaign Laid the Groundwork for Hybrid Warfare

While Russia’s full-scale ground invasion began in February 2022, the Kremlin has been using cyber tactics to prime, destabilize, and coerce Ukraine since at least 2013, if not earlier. Russia has long waged a coordinated campaign of cyberattacks on government targets and information operations and has used cyber sabotage of critical infrastructure alongside its ground and air operations in Ukraine. Integrated cyber tactics used in Eastern Ukraine a decade ago foreshadowed Russia’s hybrid approach to warfare in 2022.

Spurred by the 2013 Maidan Revolution—a popular movement that shifted Ukraine into closer political alignment with the European Union and NATO—Russia began using cyberattacks to paralyze, discredit, and distract political opponents. Russia launched distributed denial-of-service attacks, for example, to offline the Maidan movement in 2013 and to take down government computer networks and communications in 2014, likely to distract from Russian troop presence in Crimea days before an internationally denounced referendum on annexation. Russian operatives also hacked Ukraine’s electronic vote-counting system, delaying the results of the October 2014 parliamentary election.

In parallel, the Kremlin launched information campaigns on mainstream and social media aimed at priming local communities to support annexation. Russian-sponsored media, bots, and troll farms evoked and manipulated historical anxieties and divisions by connecting the pro-Western Maidan movement with a 20th-century Nazi collaborator and portraying Russia as the protector of all ethnic Russians and Russian speakers. International disinformation operations by Russia sought to deter and delay a response from the Ukrainian government and the international community by portraying Russian-backed separatists in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea as home-grown freedom fighters. These coordinated campaigns demonstrated Russia’s capacity and willingness to deploy cyber tools to exploit and amplify societal divisions before, during, and after ground activity.

Even after Russia’s ground operations in Eastern Ukraine and Crimea cooled in 2014, Russian cyber efforts to destabilize Ukraine and discredit the democratically elected government in Kyiv continued and were focused increasingly on sabotaging critical infrastructure. In 2015 and 2016, Russian hackers targeted distribution substations near Kyiv, disrupting power supply to hundreds of thousands of residents for hours, impacting communications, emergency services, and other infrastructure. Russian malware targeted Ukraine’s financial systems in 2017, causing around $10 billion in global damage. These far-reaching attacks, including the first-ever publicly acknowledged digital attack that caused a power outage, showcased the destabilizing potential for threat actors to exploit vulnerabilities in the online networks of critical infrastructure to inflict harm on, and incur costs from, civilians.

Cyber Operations Ramped Up Preceding Russia’s Full-Scale Invasion

The increase in number and scope of cyberattacks in Ukraine signaled a new phase of hybrid warfare.

Data sources: Microsoft, Microsoft, CNN

Cyber operations intensified in frequency and scale in the months leading up to Russia’s full-scale invasion. From July 2020 to July 2021, Microsoft found that 19 percent of the global nation-state threat activity warnings they issued were made to customers in Ukraine, second only to the United States in that time period. On February 24, 2022, Russia launched its full-scale military invasion of Ukraine alongside a cyberattack on satellite modems that disrupted Ukrainian military communications. Since then, Russia has used coercive tactics—including DDoS, wipers, defacements, deepfakes, and scam emails—in an effort to discredit Ukrainian government targets, erode public trust, and demoralize Ukrainian society. At times, cyberattacks have coincided with kinetic action, for example, when Russian military strikes and cyberattacks targeted government agencies in Dnipro simultaneously on March 11, 2022. However, the ways and extent to which Russia is consistently aligning its cyber and kinetic strategies are yet to be fully determined.

Cyber operations have concurrently targeted civilian critical infrastructure. According to Microsoft data, from February 2022 to October 2022, 55 percent of the Ukrainian targets hit by Russian wiper malware were critical infrastructure organizations, including energy, water, emergency services, and health care. In April 2022, Ukraine thwarted a Russian attempt to take over electrical industrial control systems with the potential to knock out power to 2 million residents. All of this has occurred against the backdrop of an ongoing anti-Western, pro-Russian disinformation campaign within Ukraine and Russia, such as social media posts claiming that Ukraine was about to surrender unilaterally. In parallel, the Kremlin has worked to undermine international support for, and solidarity with, Ukraine, for example, by accusing Ukraine of using child soldiers and claiming that Russian-speakers in Eastern Ukraine have been subjected to genocide.

How Attribution Challenges of Cyberattacks Can Undermine Diplomatic Consensus and Decisive Response

As Russia’s operations in Ukraine have shown, there are many challenges to attributing cyber operations accurately and verifiably. Some attacks—those for surveillance, for example—can go undetected or unreported for long periods of time, thereby complicating a timely identification and counteraction strategy. Moreover, governments may choose to rely on proxies such as cyber mercenaries to deflect attention and maintain plausible deniability. They may also be constrained by intelligence-sharing protocols, while private organizations may be disincentivized from sharing perceived failures in their cyber defense capabilities. Barriers to making provable attributions and compiling evidence of attacks by public- and private-sector actors have the potential to undermine the swiftness and proportionality of diplomatic or military responses.

As international humanitarian law on conduct in armed conflict predates the proliferation of cyber operations, even when attacks are identified and attributed, a lack of agreed-upon and established international norms and legal frameworks to address cyber warfare poses a challenge. The Tallinn Manual represents a notable attempt by academics and practitioners to clarify concerns and codify approaches to cyberspace norms. Additionally, multistakeholder dialogues and working groups have been established at the regional, national, and supranational levels, including the United Nations’ long-running Group of Governmental Experts and its more recently established (and Russian-supported) Open-ended Working Group, both of which seek to establish norms of behavior and the application of humanitarian law in cyberspace, and the U.N. Department of Economic and Social Affairs Internet Governance Forum (IGF). These initiatives provide the basis for greater international engagement and cross-sectoral collaboration to develop practicable approaches to mitigating and countering cyber operations and hybrid warfare.

Looking Ahead

Cyber operations have proven to be viable and effective weapons in the arsenal of state and nonstate actors worldwide. In addition to their strategic advantages—particularly ambiguity around attribution and proportionality of response—cyberattacks can be highly destabilizing and magnify the effects of kinetic warfare. As such, open, communicative, and collaborative relationships between the private and public sectors are crucial to anticipating, identifying, deterring, and responding to cyber operations, especially as social networks, hardware, and broadband internet serve as the vectors of many attacks.

The whole-of-society impacts of cyber operations call for a whole-of-society approach to deterrence. To that end, coordination across government, industry, and civil society stakeholders will be critical in Ukraine and beyond. Furthermore, developing global policies and guidelines on attribution, response, deterrence, and accountability on cyber operations will be critical to ending impunity, protecting national security, and creating international stability in the face of future hybrid warfare.

By Avery Parsons Grayson (Senior Policy and Risk Analyst), Isabel Schmidt (Senior Research and Policy Analyst), and Dr. Mayesha Alam (Vice President of Research).

This issue brief was produced by FP Analytics, the independent research division of The FP Group, with financial support from Microsoft. FP Analytics retained control of the research direction and findings of this issue brief. Foreign Policy’s editorial team was not involved in the creation of this content.